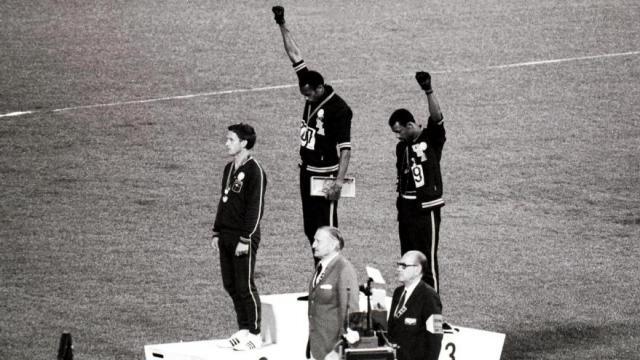

50 years ago, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in Mexico City

Advertising

This is one of the most famous photos of the 20th century, that of the 200m podium at the Mexico City Olympics, two black-gloved fists that pierce the Olympic night, those of American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos respectively gold and bronze medalists over the distance, this Wednesday, October 16, 1968.

It is an iconic photo, because it symbolizes a fight that calls the world to witness and still finds, as we will read later, a certain echo fifty years later: the struggle of African-Americans for more equality and justice in an America which is not yet rid of its old demons. As always in this type of event, everything is a matter of context and that of 1968 is explosive in the United States: the Vietnam War where the Americans are bogged down, the university campuses where the protest extends and racial tensions always vivid, exacerbated by the assassination of Martin Luther King on April 4 in Memphis.

From Prague to Paris, from Belgrade to Warsaw via Londonderry and Tokyo, part of the planet suffered a fever in 1968 and Mexico City was no exception. Ten days before the opening of the Games, scheduled for October 12 to 27, the military fired on demonstrators in the Place des Trois-Cultures, a bloody repression of the student movement which killed 44 people according to the official report, but around 300 according to the foreign media present in Mexico, including the famous Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, injured during the clash.

On the tracks too, things were heating up in 1968, especially in the sprint. On June 20, during the United States Athletics Championships in Sacramento, the 100m world record was equaled or beaten five times in the space of two and a half hours, an evening since called "The Night of Speed in which the Frenchman Roger Bambuck participates, short corecordman of the world with a time of 10 seconds over 100 m, time beaten a little later by Jim Hines, Ronnie Ray Smith and Charlie Greene, all three credited with 9 seconds 9 tenths in manual timing . The mythical barrier of 10 seconds over 100 m is crossed for the first time!

An electric climate

As a result, Tommie Smith's victory over John Carlos in the 200m final (in 20 seconds 3 tenths against 20 seconds 4 tenths) went relatively unnoticed that evening, because Smith had already been the world record holder for the distance since 1966, in a time of 20.0 achieved on this same track at John Hughes Stadium in Sacramento.

During an altogether meteoric career, the man who was then a sociology student at the University of San José would hold simultaneously between 1965 and 1968 nine individual or collective world records [200 meters and 220 yards with turns, 200 m and 220 straight yds, 400 m and 440 yds, relay 4x200 m, 4x220 yds and 4x400 m; editor's note], the most breathtaking performance for many specialists being his 200 m and 220 yards in a straight line completed in 19 seconds 5 tenths on May 7, 1966 in San José, half a second better than the previous mark on this distance rectilinear now fallen into disuse.

Invincible on the half-lap, the tall Tommie (1.91m) was nevertheless beaten and even dispossessed of his 200m world record three months later by John Carlos who signed, on September 12, a 19.92 (we switched to electric timing to the hundredth of a second) during the American selections for the Games which are taking place at Echo Summit, a town in the Sierra Nevada located at an altitude of 2,249 m, a deliberately high site perched to prepare for the better US athletes in the rarefied oxygen of Mexico City (2,240 m). It is therefore a well-prepared American athletics team – the best of all time, according to John Carlos (twenty-eight medals, including fifteen gold, along with eight world records in the Aztec city) – which presents itself a month later. later in Mexico, but not necessarily the most homogeneous.

As in the country, tensions exist between the blacks and some whites of the team, who are also totally absent from the sprint events. The idea of boycotting the Games as a sign of protest germinated for a while in the minds of some, sensitive to the discourse of the revolutionary movement of the Black Panthers and also revolted by various events that occurred during the year, in particular the exclusion of the University of El Paso (UTEP) of eleven black athletes – including long jumper Bob Beamon – who had refused to face the segregationist Mormons at Brigham Young University (BYU), days after the assassination of Martin Luther King, in April. Boycotting the Games in Mexico, Tommie Smith had already thought about it before by joining, in October 1967, the Olympic Project for Human Rights founded by Harry Edwards, a young sociology teacher whom he met on the campus of the University of State of San Jose.

Action instead of boycott

This “Olympic Human Rights Project” is an organization to protest against segregation and racism in sport. It makes four demands in particular: that South Africa and Rhodesia (future Zimbabwe) be banned from the Olympic movement, that Mohammed Ali recover the title of heavyweight world champion which had been withdrawn from him, that Avery Brundage resign from his position as IOC President and for more African Americans to be hired as assistants in school and college sports.

Himself a former discus thrower and now a recognized sociologist, Harry Edwards also wrote The Revolt of the Black Athlete in 1969, a reference work in which he involved Smith and Carlos, but also the boxer Mohammed Ali and basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, other sports legends. Rather than boycotting the Games, Smith, Carlos, but also their friend Lee Evans, future Olympic champion in the 400m, had another idea in mind: to use this superb platform offered by the Olympics, now broadcast on Mondovision, to express their anger to the face of the Earth. Provided of course to get on the podium, which they do not doubt for a moment.

Special correspondent for the daily L'Équipe in Mexico, himself a former international sprinter and future writer, Guy Lagorce is one of the first journalists to suspect that something is going on, as he recounts a posteriori in an article du Monde published in September 2000: “The African athletes, he wrote, warned me on the first day: 'Come quickly to the Olympic village, things are happening. Usually, black Americans hardly speak to us; this year, they call us “brothers”, buy us our boubous, our necklaces, and they all wear a button with “Project for Human Rights” written on it. »

"In the village, continues Guy Lagorce, I will find John Carlos, a sprinter whom I know well, and who confides to me: 'We are going to protest against the fate of blacks, against the indignity in which they are held in United States and many other countries around the world. The United States of America is only united in name, since not all citizens are treated the same. That's why here we don't represent the United States, but the black people of the United States.' »

“The speech is firm, but calm, continues Guy Lagorce. Not an ounce of excitement. That's what strikes me the most. I ask Carlos what type of demonstration they are going to engage in, he and his friends. He smiles and is content to say: 'You will see it well, you will be millions to see it.' »

At the start of the 200m final, however, Tommie Smith did not lead far. In the first semi-final, John Carlos clocked a slightly better time than his – 20.12 against 20.14 – but it was mainly pain in the groin and upper right thigh that occurred after crossing the line finish of the second semi-final which bothers him. He even considered giving up before his coach, Bud Winter, reassured him and applied ice packs to the sore area. “At the exit of the bend if I am unscathed, you will have to come and get me. They can still dream" he says to himself, as recounted by former Europe 1 radio journalist and writer Pierre-Louis Basse in 19 seconds 83 hundredths, his 130-page essay devoted to this single race and also to its own childhood memories.

Closest to Usain Bolt

Confirmed in his hope of winning gold after his fine semi-final, in the final John Carlos set off like a dragster from lane number 4 and even came out quite clearly in the lead of the bend halfway through the race. Reassured for his part that his thigh held in the curve, Tommie Smith can then, as he had planned, place his acceleration. He's in lane number 3 and has Carlos right in front of him, in his sights. With his magnificent long stride, he passes in front of his compatriot without breaking up 50 m from the finish and gets up fifteen meters from the line, raising his arms to the sky. He is an Olympic champion!

Bewildered, John Carlos did not even see the Australian Peter Norman coming to lane number 6, Norman beating him in the last meters for the silver medal in 20 seconds 06 hundredths, the time remaining, at this day, the Oceania record for the discipline. Carlos will have to settle for bronze in 20.10. The race was superb and the winner's time was no less: 19.83, a new world record!

Immediately, or almost, the question that will plague statisticians for decades will begin to arise: what time would Tommie Smith have achieved if he had not gotten up fifteen meters from the finish? Even the great French specialist in sprint technique Pierre-Jean Vazel, whom we reached on the phone, has trouble deciding. "It's hard to say to the nearest hundredth. But it made him lose between 10 and 15 hundredths. So I think it was a little better than Mennea's record, "he says, referring to the 19.72 achieved eleven years later by the Italian Pietro Mennea, on this same track in Mexico City, September 12, 1979. By extrapolating a little, we are therefore entitled to think that Smith would have run in 19.70 if he had not gotten up and that his record would undoubtedly have held for nearly thirty years, probably until 19.66 made on June 19, 1996 in Atlanta by Michael Johnson, during the American trials for the Games.

A great admirer of Tommie Smith, Pierre-Jean Vazel even indulges, when pushed a little, in the game of comparisons to estimate: “Yes, we can compare him to Usain Bolt. It's the one he comes closest to. Not at the level of the charts of course, because Tommie Smith stopped racing at 24 years old. But in terms of style and stride, yes. He and Bolt are really, really close. Bolt being the ultimate reference, the opinion of Pierre-Jean Vazel situates the athlete and the performance.

As for why Tommie Smith got up so early, we have to go back to the book 19 seconds 83 hundredths by Pierre-Louis Basse, in which the champion had confided in December 2005, when a gymnasium in his name – the first in the world – had been inaugurated in Saint-Ouen, in Seine-Saint-Denis, near Paris. It's because on that evening of October 16, 1968, Tommie Smith constantly kept segregation in mind. And this barrier which, in the buses, separated the Whites and the Blacks.

Two exclamation fists

“Hold on tight, Pierre,” he confessed to Pierre-Louis Basse that day in Saint-Ouen. I was thinking about it during the race. I thought about it at first, when I got up. I was thinking about it on the bend, with, by my side, that thug John [Carlos; editor's note], gone like a grenade unpinned. I thought about it through and through. They could even add more to me. To tinker myself with a 220 yards in a straight line, I would have continued to think all that. Just at the end, when I realized, 15 meters from the wire, that I had won, I really couldn't help but get up.

Moment of ecstasy and end point, he already knows, to his career as a sprinter which will end there, at only 24 years old. He already knows what happens next, he has imagined the scenario, but perhaps he hasn't grasped all the repercussions that his gesture and that of John Carlos, just now, on the podium, will have, and he doesn't yet know that Peter Norman, the Australian silver medalist, will join in his own way, in their gesture of protest.

An hour and a half later, the three recipients meet in the appeal room, for the prelude to the medal ceremony. Pierre-Louis Basse recounts the scene in his book: “Peter Norman had attached to his green tracksuit the famous badge distributed by American runners: The Olympic Project for Human Rights. The scene was quite unique. Tom and John were engaged in a sort of medal rehearsal. Maybe they were about to share the two black leather gloves. Gloves bought by Denise, Tom's partner, in a supermarket. So Peter approached them. John Carlos looked at him with a peculiar pout – a well-known mix of banter and defiance: 'keep it out, mate'. Then, Tommie Smith looked at him gently from the height of his 1.91 m: 'Are you a believer, Peter?' 'Sacrement' replied the Australian who had already wondered why in his country several million Aborigines had been liquidated. 'The gloves, you would do well to share them'. 'Good idea, Peter'. Tommie passed the left glove to John. He kept the right”.

This medal ceremony will go down in history, immortalized by the famous photo which will go around the world and which still persists in memories, 50 years later. “We will appear on the podium in socks to denounce the poverty of black people, provided Tommie Smith. My scarf tied around my neck and John's necklace will evoke the lynchings carried out in the South. And our gloved fists will represent the strength and unity of black people. »

When the American anthem sounds, Smith and Carlos raise their fists to the sky as expected. And they remember. Smith from growing up in California where his parents emigrated from Texas hoping to provide a decent life for their twelve children (Tommie is the seventh) while trying to "never look poor". Carlos from his Cuban parents who raised him on the other side of the country, in Harlem, where he experienced the riots of 1964: one death, 118 injured and 465 arrests. In front of them, standing at attention, Peter Norman can see nothing of the scene. But he knows full well what's going on behind his back and he nods in his own way, sporting the Olympic Project for Human Rights badge on his green track jacket. From now on, the three men will be linked for life.

Panic in the Olympic Village

As soon as the ceremony is over, trouble will begin. Smith and Carlos go out under the whistles. Guy Lagorce, L'Équipe's special envoy, renewed contact with John Carlos a little later and the latter declared to him: "We have won medals and received applause, but the majority of white people believe that we, the Blacks, we are animals, insects that do not think. When we do what they want, white people treat us like good boys. In fact, they think of us as race horses to whom we give a sugar every once in a while. We are tired of all this. We wanted to say to white people: take an interest in all of our problems and not just in the way we run or jump. ".

The next day, Thursday October 17, at noon, Douglas Roby, president of the American Olympic Committee, announces to Smith and Carlos that they are excluded from the Games and that they must leave the American delegation within 48 hours. And he adds that if this decision is not implemented, the International Olympic Committee, led by American Avery Brundage, will suspend the entire United States team.

From then on, the tension went up a notch. Some black athletes, says Guy Lagorce, tear off the USA letters sewn on their clothes and decide to leave the Games. In reality, two camps are opposed: those who support the action of Smith and Carlos and those who condemn it, with blacks and whites in both camps, it must be specified. Jesse Owens, the hero of the Berlin Games in 1936, is called to the rescue to calm things down.

Finally, only Smith and Carlos will leave the premises and the protesting athletes will continue the competition. Two of them will feed on their anger to explode with rage two world records that will last two decades: Lee Evans in the 400m (43.86) and Bob Beamon in the long jump (8.90m), mind-blowing performances for the time, even if they were partly attributed to the high altitude of Mexico City. In support of their comrades, Lee Evans, Larry James and Ron Freeman stand on the all-American 400m podium wearing a black beret, while sporting a broad smile "because you don't shoot a man who smiles" will say Evans, who fears the mad act of a crank.

Excluded from the village, Tommie Smith and John Carlos wander through Mexico without a penny in their pocket. It is their wives who pick them up and pay for hotel and taxis. For them, a long Way of the Cross begins. In the country, the press, even that reputed to be progressive, falls on them by evoking a “national offense”. The Los Angeles Times, for example, goes so far as to compare their gesture to the Nazi salute. Racist insults rain down on them when they are in public, they receive death threats by mail or telephone and, as they are suspected of working for the Black Panthers, the FBI tracks them and interferes in their lives. private.

Both will still make a brief stint in American football in 1969, but without much success, because Smith injured his collarbone and only played two games with the Cincinnati Bengals while Carlos, injured in a knee, does not play any with the Philadelphia Eagles. The two medalists from Mexico will now have to make do with odd jobs, haphazardly moving constantly.

Insults to redemption

Having returned to the ranks and for a long time silent about their gesture and its consequences, they will end up finding positions more in line with their skills: Tommie Smith as a university coach in Ohio then in Santa Monica in California; Carlos as a representative at the Puma brand, then sports advisor in a school in Palm Springs, also in California. Their couples will not resist this bohemian life. Smith would divorce twice and Kim, the first wife of John Carlos, would commit suicide in 1977 after receiving compromising photos of her husband in the company of other women.

A discreet actor on the Mexico podium, Peter Norman will not be much better off once he returns to Australia. The sports authorities of his country and part of the Australian public opinion accuse him of having associated himself with the gesture of Smith and Carlos. And although he achieved the minima, the Australian Olympic Committee refused to select him for the Munich Games in 1972. The tenacious grudge, this same committee "forgot" to invite him to the ceremonies of the Sydney Games in 2000. bronze statue of him will finally be erected outside Melbourne's Lakeside Stadium next year, a belated move by the Australian Olympic Committee, which made the announcement last week and also awarded Peter Norman as posthumously, the Order of Merit for his contribution to the world of sport.

When Peter Norman died of a heart attack in 2006, Tommie Smith and John Carlos did not hesitate for a second to make the long trip to attend his funeral. They are even among those who carry his coffin to Melbourne, leaving the church, to pay their last respects to the one who had become much more than a friend.

In the meantime, mentalities had fortunately changed in the United States. As the legitimacy of the civil rights fight became apparent, Smith and Carlos' gesture became a matter of pride, not shame. “We finally understood, confided Tommie Smith to the journalist of Le Monde Annick Cojean in 2014, that my fist contained neither hatred nor mistrust. On the contrary ! I was expressing the hope that this country would amend its system! I did not turn my back on the flag. I was facing him! Proud to be a black American. »

From pariah, the two men have transformed over time into heroes in the eyes of a large part of public opinion. They each signed a book, Tommie Smith Silent Gesture and John Carlos The Sports Moment That Changed The World to testify to their experience. As a sign of recognition, on October 17, 2005 the State University of San José, which had ostracized them for a moment, had a monument erected on its campus representing the two athletes raising their fists on the podium in Mexico City.

An even more dazzling symbol of their redemption: they were received at the White House by Barack Obama on September 29, 2016. For the first black president of the United States, it was a question of paying homage to them, but also of signifying somehow their fight wasn't over. In response to numerous racist acts and countless police brutalities, the Black Lives Matter movement was born in July 2013, after the acquittal of police officer George Zimmermann accused of having wantonly killed a teenager. black named Trayvon Martin, Florida.

Inspired by Smith and Carlos, San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick has since become a symbol of the fight against discrimination and police violence in the 21st century by kneeling during the American anthem which resounds in the stadiums before each match. If his gesture, considered provocative, cost him his place in the National Football League, where the club owners have arranged among themselves so that he does not find a team, Kaepernick has just been hired by Nike to become his figure of bow. This marketing move caused Nike shares to soar on the Wall Street stock exchange despite a smear campaign that saw Americans burning their Nike shoes in spite. Fifty years later, if mentalities have evolved, the fight of Tommie Smith and John Carlos continues, with sport still as the most visible vector. Read John SMITH's interview below ►►►

John Smith testifies: “it took a lot of courage for them to do such a thing”

Former talented sprinter – selected for the 400m for the Munich Olympics in 1972, he had to give up at the last moment due to injury – and best known in France for having been the trainer of Marie Josée Pérec and Maurice Greene, among others , John Smith remembers the impact Smith and Carlos' gesture had had in the United States. Testimony.

John Smith, you were a student at UCLA in 1968, can you give us the context of the time? Yes, in 1968, I was just starting at UCLA. At that time, we were in full awareness and in full upheaval. There was the Vietnam War, the emergence of the hippies, the “flower children”, Woodstock, the counter-culture etc. To tell the truth, it was a period when people felt the need to express themselves. The Watts Riots [August 1965; editor's note) had taken place three years earlier, followed by the Detroit riots [July 1967; editor's note] and New York [after the assassination of Martin Luther King in April 1968; editor's note]. Blacks were showing their opinions. Most people don't like to talk about it, but there was still semi-apartheid in the United States too. We were reaching a critical moment, the situation was ripe for it to explode. We wanted to be heard but it wasn't just black people. Many whites were sympathetic to our cause.

Did you know Tommie Smith and John Carlos well? I did know them well, yes. I knew John Carlos when I was in high school and I knew Tommie too even though we weren't close then. I remember doing the Coliseum relays (from Los Angeles) when I was a kid and Tommie was doing it. I was proud because we had the same name: Smith. Tommie was someone with a real social conscience and so was John Carlos. John was from Harlem. He had seen a lot of things, including the riots in Harlem in 1964. Tommie came from Texas but he then moved to California. He had worked in the fields when he was young but his mother made sure that he and his sisters and brothers received a good education at school. Tommie has a master's degree in sociology, I don't know if he doesn't also have a doctorate. So he was very educated. Carlos was very talkative, very eloquent, while Tommie tended to internalize things. But when he decided something, he remained firm on his positions. He was very determined when he believed in something.

What did they mean to you? To me, John Carlos and Tommie Smith represented two strong black men that we all respected. And it still is today. I still have respect for them. I was impressed because they were doing but I also understood that when you believe in something and defend your values, you know there will be consequences. And at that time, the most important thing was that things change. They really put their lives on the line to make people aware. It was a social statement. But Peter Norman too was ostracized when he returned to Australia.

Did their gesture change you, personally? I can't say that their gesture changed my way of seeing things. Although a teenager at the time, I had taken part in the Watts riots [in 1965; editor's note]. On the other hand, it did me good to see someone express themselves in this way. And on such a stage, in front of the whole world! But it was also a gesture of protest. And challenging isn't something that necessarily makes you feel good about yourself. It was certain that there were going to be good and bad reactions. When you push a company into a corner, it speaks! It can bring change. Change and progress go hand in hand and that's a good thing.

How did you experience this Mexico City event and what did you think of it? I remember watching the medal ceremony live on television on the UCLA campus. Everyone looked at me and said “wow, the cow! ". People sometimes ask me if I would have done the same thing in the same situation and I always answer “I don’t know! ". It is something that came to them from the bottom of their hearts. I've never been in this position, so my answer is, "I don't know!" It took a lot of courage for them to do such a thing. I remember how they were greeted when they came back. They received threats, crosses were burned in front of their houses. I can't remember which one but one of the two had his dogs killed. They were threatened with death, they both had to divorce. It cost them dearly. And I'm not just talking about money. It weighed on them and their families and brought out all the racism in the United States. People took revenge on them.

Despite the scope of their gesture and even if the situation has evolved, everything is not settled, far from it. We see what is happening right now with Colin Kaepernick… Fifty years later, no, everything is not settled. The rich got richer. But athletes are making money now and can make good decisions. They have a choice. Tommie Smith and John Carlos had no choice. Look at LeBron James: he founded a school. Many athletes redistribute to their community, organize programs to serve as mentors to young people. I believe that now that top athletes are getting rich, it is their turn to bring about change and have an impact. One of the reasons I became a coach is that I can have an impact on young people. Now I even have former athletes of mine who have become coaches. It is important to transmit. During the 1960s, we fought our struggles. It's a different fight today. Young people have resources at their disposal that we did not have, such as social networks Instagram, Snapchat etc.

It's still incredible that movements like Black Lives Matter still need to draw attention to injustices, isn't it? It's a different fight. There's no point destroying your neighborhood. But when one fight ends, another replaces it. People are always looking for more justice and equality. It is much more transversal now than in our time. But when you kill a certain class of society [he refers to Black Lives Matter, Editor's note], you have a problem. We still need to be heard. Slavery has been abolished but there are still sufferings like the ones you mention. I want to stay optimistic. First, you need to stay alive to make changes. You cannot kill yourself or allow yourself to be killed. You will always be stronger alive than dead because alive you can make your voice heard. If you are a known athlete and want to bring about change, you have money to bring about change. If you get killed, you just become a stat. If you really want to change society, go to law school, business school, create something useful and you will become the voice of those who have no voice. But above all, by becoming rich through sport, do not become what you hate. You have to stay progressive.

NewsletterReceive all the international news directly in your mailbox

I subscribeFollow all the international news by downloading the RFI application